Louisville isn’t particularly unique in it’s history - a city founded along a river, it functioned as an important stopping point for ships on the Ohio, and eventually built its own extensive industry. Over decades, a dense urban core formed. This core would eventually decimated by a combination of redlining, incredibly racist city plans, urban renewal, and urban highways. These factors would lead to a city with a hollowed out urban core, largely designed for middle class commuters that don’t live in it, while neglecting the poorer, minority populations that do.

This history may not be unique, but Louisville’s response to it’s history is somewhat, at least in the past couple decades. The urban core of the city, which lays inside the I-64 expressway, has failed to keep up with it’s peers. While Nashville, Cincinnati, and other similarly sized cities seen somewhat of an urban renaissance, Louisville’s urban core has remained largely stagnant. The occasional large developments we do see often fail to meet expectations. The real question is - why is this happening?

Dictatorship of the Automobile

The auto-centric nature of Louisville becomes apparent when you try to trek any of the city by foot. Despite some good work put in by groups like Streets 4 People, our Vision Zero campaign, and more, Louisville’s streets remain profoundly unsafe for anyone not in a car. Pedestrian and bicyclist deaths have been on the rise since 2018 according to the city’s Vision Zero Dashboard. This, along with the suburban nature of most of Louisville, results in the city being incredibly difficult to traverse by foot outside of a few small areas.

This is happening entirely because the city is not designed with the pedestrian in mind. Sidewalks and pedestrian infrastructure can often be found in a state of disrepair, if these things are even designed into a streetscape at all. Other cities are seeing large scale investments into people-focused infrastructure, Cincinnati has it’s own team dedicated to building pedestrian infrastructure. Louisville does not have an equivalent level of investment, our pedestrian infrastructure is often a rounding error in the city budget. This keeps Louisville largely unwalkable.

Walkability is crucial to the vitality of an urban area. Walking is incredibly beneficial to personal health, reducing disease. It also has a profound effect on social and public health, with chance encounters between friends and neighbors being more likely. The benefit the city government would care about the most, though, is that walkability has been shown to be very good for business. Walkable areas also tend to be denser, which means a higher density of well-performing businesses for the city to collect some delicious tax revenue.

The roads themselves are also a major problem. Jeff Speck talked at length in his recent visit to Louisville about how our urban roads incentivize dangerous driving. Our city is enthralled with large, one-way streets that essentially become drag strips. One way roads subconsciously make drivers drive faster since nothing is coming towards them in the the opposite direction. Many roads also lack street trees or have minimally used street parking, both of which slow down drivers by taking away space from them. This makes roads unsafe for road-users, whether it be cars, buses, or bikes. Dixie Highway is the perfect example of this, one of the most dangerous roads in Louisville, it is often called Dixie Dieway.

The traditional streets and roads aren’t the only manifestation of car dominance. The largest ones are the expressways that we have rammed through our urban center, two expressways cut Louisville into pieces. These expressways have a myriad of negative effects: triggering health problems, reducing connectivity, creating dangerous intersections at off ramps (looking at you St. Catherine), and taking up massive amounts of valuable urban land. The orientation of our expressways also cut us off from accessing our own waterfront, relegating many of our waterfront events to take place under the interstate, having us inhale the fumes of thousands of polluting cars.

Spaghetti Junction is the primo example of ugly urban highways, to the point of national recognition. An ugly concrete mess of pasta that no one likes to deal with.

It should also not be forgotten that our interstate highway system was not originally meant to go into the cities themselves. These largely exist in our cities for the sole purpose of destroying or dividing minority communities, and they still do so to this day. It is impossible to ignore how we allow something with explicity racist purposes to control our city more so than our own citizens.

Micromobility and Public Transit

Alternative transit options to cars are simply not accessible for most Louisville residents, at least in a practical sense. Louisville, as of summer 2024, has a grand total of 1 mile of protected bike lanes. This does not include the Louisville Loop, but the Loop bikeways are far into the suburbs, unfinished, and largely used for recreation. This is not surprising considering metro’s budget for bike infrastructure rarely tops $500,000 annually.

Perceptions of safety are extremely important for cyclists, and a lack of safe infrastructure in Louisville has made the total amount of bike commuters likely less than 1000 total. Bike infrastructure isn’t just used for bikes; mobility chairs, e-scooters, and other micromobility vehicles also utilize them, and the lack of dedicated, protected infrastructure in the urban core makes all of them difficult or deadly to use

Public transit isn’t any more accessible than cycles or scooters. TARC’s current woes are well known, facing a fiscal cliffs and route cuts, things are not looking up. Even before the cuts, none of our bus routes are particularly enticing if you don’t NEED to take the bus. The best you are getting is 15 minutes between buses, and even then they are often late. This isn’t completely TARC’s fault. Louisville is a very large city with extensive, low-density suburbs. It is seen as inequitable if TARC does not serve as much of the city as possible, but many of it’s far-flug suburban routes have incredibly low ridership. This service model has, evidently, become unsustainable, largely due to how our car-centric urban form has incentivized intense sprawl.

The Crippled Third Place

The third place is a term often thrown around in urban planning circles. It essentially means any place you can hang out at that isn’t your home or work such as libraries, coffee shops, and bars. The third place in Louisville has a major accessibility problem due to the car-centric infrastructure and lack of mobility issues mentioned in the last two sections.

Many of our largest, nicest, and newest third places are inaccessible if you don’t want to drive. Our newest libraries, Northwest and Southwest Regional, are located in Lyndon and Okolona respectively. These are two of the most suburban areas in the city, with infrequent buses at best and minimal bike access. Most of our major shopping outlets have also fled to the suburbs. St. Matthews and Oxmoor Malls are located on one of the most dangerous and generally despised pieces of road in the city: Taylorsville.

This all essentially creates “islands” of socialization in Louisville. Almost any third place you are going to want to go will require you to sail a sea of concrete and asphalt. This isn’t really fun if you are in a car, but it is especially not fun if you are trying to get to these places without a car. This is especially harmful for younger folk, as they must rely on their parents to ferry them around. This is assuming, of course, they are even let into their chosen third place at all. St. Matthews Mall was a common gathering spot for me growing up, but now has significant restrictions of minors being allowed in without parental supervision.

Zoning

Zoning laws, besides roadways, are the biggest contributor to many of the issues mentioned so far. Louisville is zoned at around 75% solely for low-density, single-family households. Single-family zoning presents a litany of logistical, financial, and environmental problems.

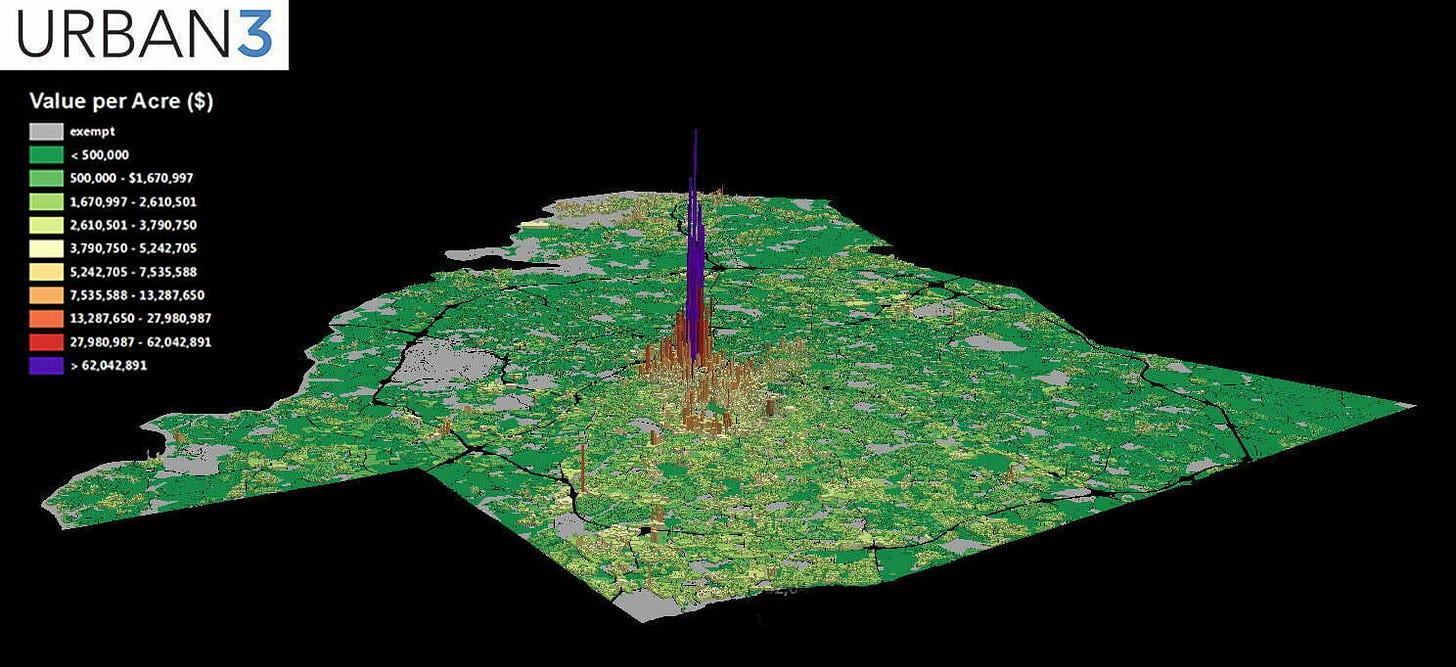

Single-family homes are more costly to deliver government services to. One building will only have one household, whereas multi-family buildings can have dozens of households, making delivery of utilities and other services much cheaper. This is especially bad when you consider that single-family neighborhoods produce signifcantly less tax revenue than their urban, denser counterparts. This is best displayed by maps made by Urban3 for other cities with similar densities.

In addition to a plethora of low-density zoning, our state legislature is actively fighting basic reforms that allow more density. Louisville’s planning department is working on “missing middle” housing reforms that would allow certain housing types: duplex, triplex, fourplex, townhomes, and cottage courts by right in single-family areas, but this is on hold now. With the state recently straight-up putting a moratorium on new zoning changes for a year, it is clear our largest enemy in this regard is likely going to be in Frankfort.

The Nature of our Nature

Our city is often lauded for it’s park system, and for good reason. We have a beautiful set of parks designed by Frederick Olmstead in the late 1800s, and a ton of nice parks built after that as well. We have spectacular bones for a world-class park system, but the issue arises with funding and maintenance. A 2023 report by the Parks Alliance showed many of our parks, particularly in areas with higher minority populations, were not receiving needed maintenance. We have been shown to spend less on our parks compared to peer cities.

City Financing and Stagnation

NIMBYs are a significant barrier, one technically not related to design in this case, but there are some issues from the far opposite side of the spectrum. It is generally not a good sign when Louisville officials have to regularly get on their hands and knees to beg developers to build new projects. This is often done through tax incremented financing (TIFs), which diverts some new tax income from a development back to the developer to incentivize development. The city recently approved a $114 million dollar TIF for the One Park North development. This is the equivalent of 10% of the city budget in tax incentives. Some tax incentives, especially for much needed housing, can be fine. Tax incentives on this scale, though, indicate that something is wrong on a structural level; this is all likely a result of the problems mentioned so far.

TIFs are one of Louisville Metro’s favorite development tools, you can see all of the city’s TIF districts here. We have a hand full of success stories such as The Omni and Axis on Lexington, but we also have ones that have done little or tremendously under-delivered such as the West Louisville TIF and the Butchertown Sports District (remember that?). Studies of TIFs in other cities show their results are mixed at best. Overreliance on tax incentives ends up painting an image of stagnation.

A City that Kills You

All of these problems, in addition to some not mentioned, do not paint a pretty picture. Louisville, as it is now, is deadly. Whether its traffic violence, long-term pollution exposure, or social isolation, our urban form is not healthy. The inevitable conclusion with such a cacophony of problems is that the city’s form has a complete indifference to it’s own inhabitants when they are outside of a car. All non-car users are seemingly worth sacrificing at the altar of auto-dependency.

Is this fixable?

Yes! I know this post has been all doom and gloom so far, but these are all very fixable problems. Louisville’s urban grid, geography, and population alone provide a fantastic base for a connected, mobile, and livable urban fabric. Things do not have to continue as they are, but we have to be aware of the large hurdles in our way. We can and should make small scale changes to improve our city, but also acknowledge the systems that will fight against those every step of the way. Nothing that stands in the way of a better city is permanent. Highways can be re-routed or removed, roads can be rightsized, zoning can be reformed.

It is also worth noting that we have some great local organizations that are pushing to actually solve many of our problems. Streets 4 People is advancing causes for safer streets. The University of Louisville has been at the forefront of a lot of good pedestrian-friendly infrastructure design on its campuses. The city planning department has been embracing reform and is moving in a very positive direction despite state intervention. TreesLouisville, LouisvilleGrows, and the Olmstead Conservancy have been doing great work for our urban greenery. Momentum is moving in a positive direction, albeit, slowly.

The problems presented so far are much more complicated, and their solutions more so. This post mainly exists to present the largest issues. In future posts, we will dive deep into specific problems, how they effect Louisville, and potential solutions.